Depiction does not equal endorsement. I am under no impression that just because a film depicts post-WWII Jewish refugees settling in Israel, it commends that decision and the creation of such a state. That being said, I believe that it is impossible to have a “nuanced” take on Israel without, at the bare minimum, an acknowledgement of its oppression of the Palestenian people. One could even hope for empathy. The Brutalist contains neither of these, and throughout its runtime, it remains entrenched in the Zionist viewpoint, going as far as paralleling Israel with self-autonomy.

Spoilers for the film incoming as well as content warnings for sexual assault.

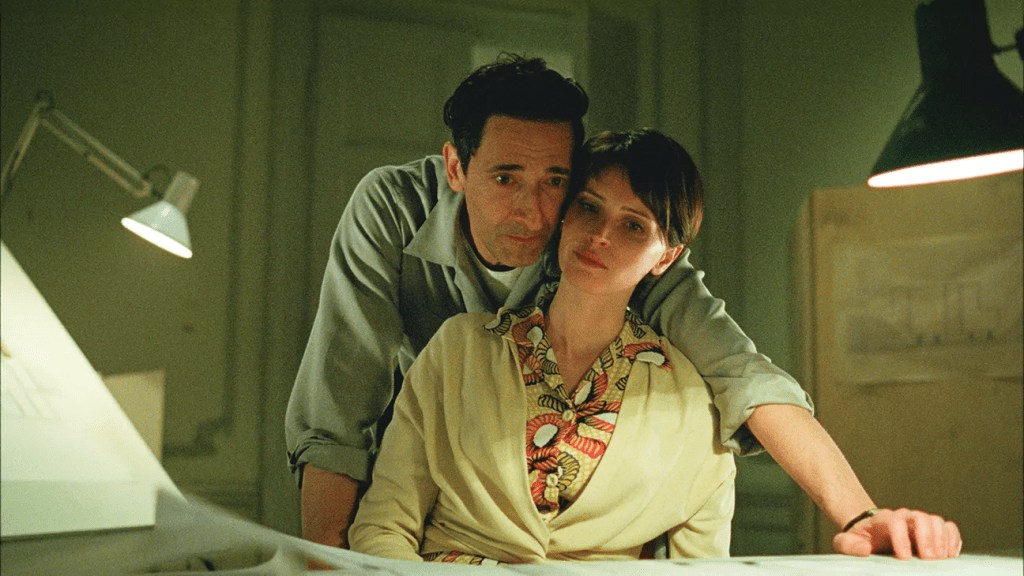

The Brutalist directed by Brady Corbet primarily follows architect and refugee László Tóth (Adrian Brody) as he attempts to make a life for himself in America after the holocaust. He captures the interest of a wealthy patron Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) who commissions him to erect a community center in a suburb of Philadelphia, at great personal strife and cost. He is later joined by his wife (Felicity Jones) who is wheelchair bound due to osteoporosis and his niece (Raffey Cassidy) who is mute, both disabilities a result of the war.

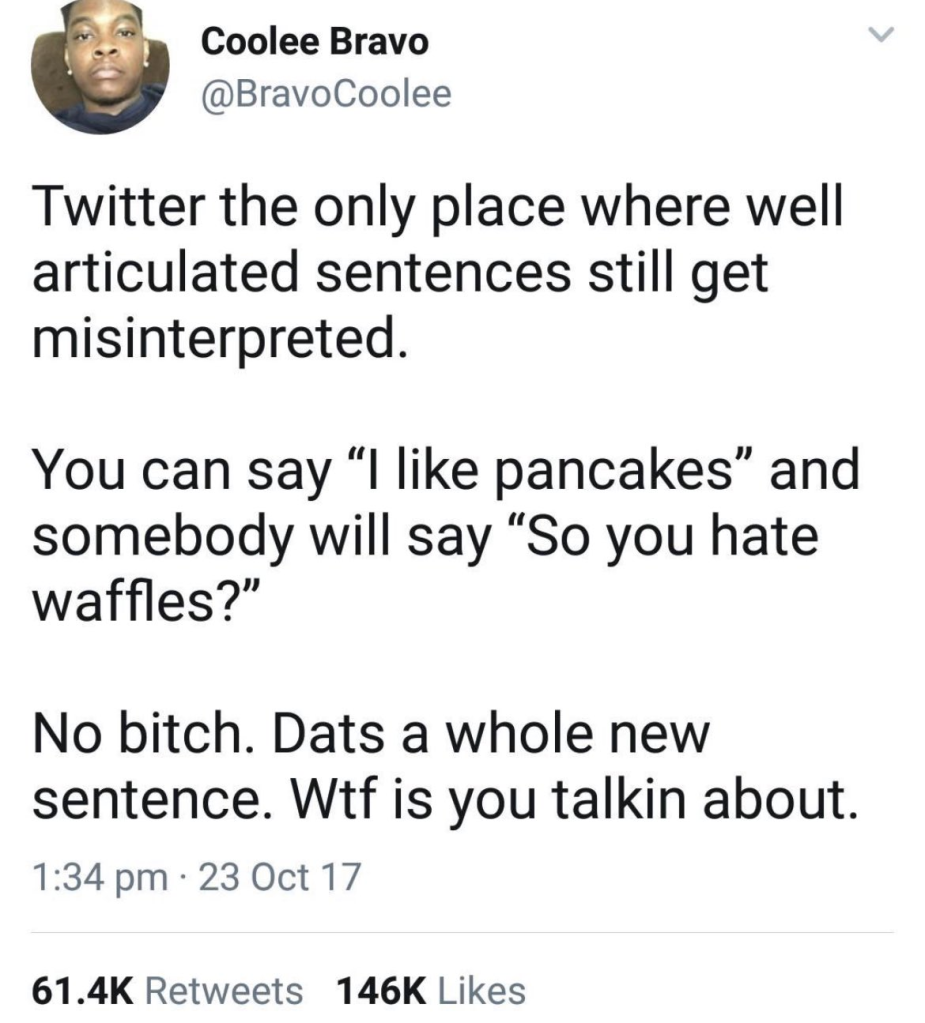

From The Brutalist‘s first mention of Israel, it is clear that the narrative would be affixed in a Zionist viewpoint. It is radio narration credited to the Zionist movement that plays over an unrelated scene and is absent from the filming script. Importantly, it specifically refers to UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II) aka the United Nations Partion Plan for Palestine, which uses the term “Palestine” in its the original document. The any of Palestine is absent from the announcement, probably as it is credited to the people of the Zionist movement. The absence of Palestine seems inconsequential, but one of the tactics of Zionists today is to refuse Palestinian autonomy by denying that there ever was a Palestine, and so avoiding the word is not only broadly ahistorical, but works towards modern day Zionist goals.

The announcement in full is:

“On the 29th of November, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael. The General Asembly required the inhbitiants of Eretz Yisrael to take such steps as were necessary on their part for the implementation of that resolution. This recognition by the United Nations of the right of the Jewish people to establish their state is irrevocable. This right is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations in their own sovereign state. Accordingly we, members of the people’s council, representatives of the Jewish community of Eretz Yisrael, and of the Zionist movement, are here assembled on the day of termination of the British mandate over Eretz Yisrael. And by our natural and historic right, and on the basis of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, hereby declare the establish of a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael to be known as the State of Israel.”

This radio announcement touches on two themes that reemerge in The Brutalist. The first is the idea of being “welcome” to a place, as the Tóths feel out of place and unwelcome throughout the film’s runtime. The second is the idea of “being the masters of their own fate” through sovereign rule, which will later be touched on along with how the film depicts self-authonomy.

At its second mention in the film, Israel becomes linked with the idea of a character’s individual self-autonomy. Perhaps self-autonomy is too tame a word, as in the film, it’s not only the ability to make choices for oneself, but a control over the body itself with functions that were thought to be out of one’s abilities. In the scene, László’s niece decides to move to Israel with her husband. This is the first time the audience hears her speak, establishing the first connection between self-autonomy and Israel’s freedom in sovereignty.

Within the same scene, László admits that he is going back to work for Van Buren after years of the project’s inactivity. His wife pleads with him not to go, pointing out how Van Buren is not good to him, but he dismisses her concerns and tells her that he will meet his employer in Italy to inspect marble for the project.

When it comes to media analysis, it is important to remember that the characters themselves do not have the free will or the rights or the graces that we reserve for actual people. A writer can only communicate his or her themes to the audience by corralling the characters into situations where their choices define their character and morality is defined by their consequences.

In the scene with László’s niece, he is given the choice between Israel and Van Buren, or rather, Israel and the film’s representation of America. He chooses his trip to Italy. On this trip, László’s is raped by Van Buren, the ultimate violation of autonomy. Israel then becomes retroactively contrasted against America as the safe option, where he would have been able to maintain his self-dignity, as opposed to how he’s punished by the narrative for trusting Van Buren.

After the assault, László becomes distant and understandibly agitated. During a heated disagreement with his wife, they both come into alignment that they’re miserable in America because they are not wanted. László points out how they had “no other choice” but to come. Behind the curtain looms Israel, a place where they would be welcomed and is now another viable option for them.

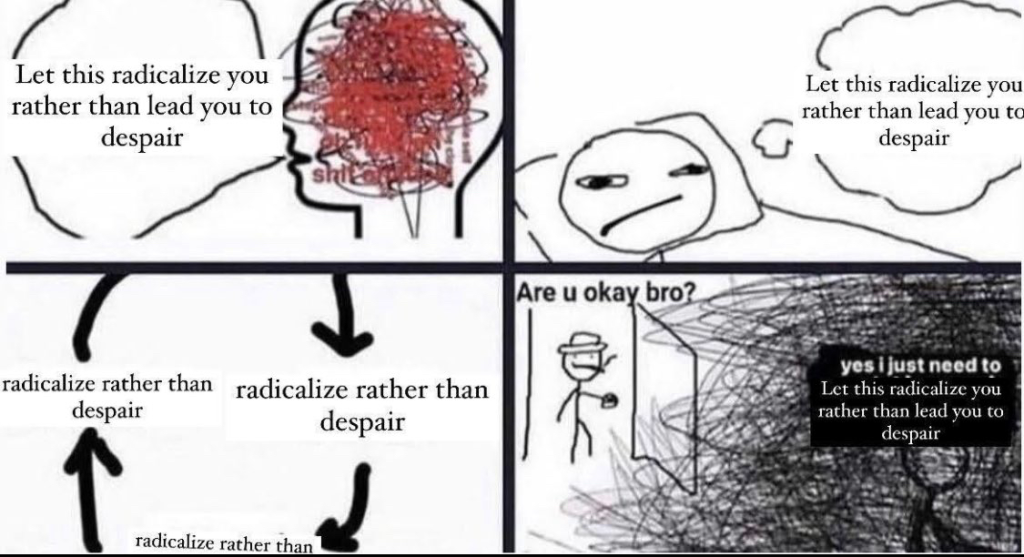

In truth, settlers are not wanted in Israel either, not by its existing residents, Palestinians. This is never mentioned in the film. Perhaps, if the movie had teeth, it would acknowledge this fact- that it does not matter if someone is “wanted” or not, but all that matters is who has the resources to protect their position, and how they create the “unwanted” in the process. How is a film meant to interrogate how its subjects are falling for a lie, when it will not even admit they are being lied to? How are we meant to see a lie without knowing the truth?

The end of the second act, and the end of the film, concludes with László wife professing that she will follow their niece to Israel. László promises to come as well. After this, his wife is emboldened to stand on her own using a walker as she confronts Van Buren and publicly accuses him of raping her husband. Once again, a clear parallel is made between self-autonomy and Israel, the inspiration of its sovereignty allowing The Brutalist‘s characters to push the limits of their disabilities.

There is a loose interpretation of events in which Israel is paralleled with heroin, as a heroin-induced euphoria prompts his wife to decide on Israel, saying it was the voice of God who spoke to her. In that case, her ability to walk could also be similar to the temporary effects of heroin. This is a weak interpretation because heroin comes up many times in the film, and never else in conjuncture with Israel. Also, the other shoe never drops. The parallel with heroin is never taken to its end. The viewer sees László wife risk death with her overdose after a singular exposure, but it never witnesses any consequences of believing in what Israel represents.

Honestly, this metaphor between Israel’s self-determination and the individual character’s self-autonomy is the most clear and consistent through line regarding Israel. Beyond its broad criticisms of America, The Brutalist seems unconcerned with actually politically deconstructing anything else.

Most of the film’s references to Israel explain why it was enticing to early settlers. America was hostile to foreign refugees, but Israel offered a place where they would be welcomed. It was a place they were meant to be “home”, to find autonomy. In the epilogue of the film, László’s Israeli niece speaks of the traumatic influences László baked into his design. He is so elderly that he is unable to speak for himself. She ends it with, “No matter what the others try and sell you, it is the destination, not the journey.”

There are two major and distinct readings of this ending.

One, Israel has co-opted the trauma of holocaust survivors to create its own narrative. László is unable to speak for himself, robbed of his autonomy, and the sentiment of “it’s the destination, not the journey” is antithetical to a lengthy film centering on a man’s struggles and trauma.

Two, László really does believe that. When asked “Why architecture?” earlier in the film, he spoke to the enduring nature of a building, the opportunity for his work to spark political upheaval long after he has been erased. Throughout the construction of the community center, he took a great number of pay cuts, of belittling and abuse, to ensure that the construction of the project was true to his vision. The destination is not metaphorical, but physical.

In truth, the journey informs the destination. László’s trauma and experience in the holocaust shaped the community center. “It’s the destination, not the journey.” in this case is both as true and as untrue as, “It’s the journey, not the destination.” Without the journey, there would be no destination. Without the destination, the journey would have been meaningless, robbing an artist of his legacy. It’s an intentionally ambiguous statement, meant to inspire a number of interpretations.

To claim this discordant end is a condemnation of the Zionism thus far is a stretch, a conclusion only likely to be reached if the viewer is already critical of the state of Israel. A truly critical film would not textually reflect major tenets of Zionism while sneaking its criticisms into subtext and ambiguity. Even neutrality would require some sort of equal footing between Zionism and its inverse.

It is important to remember that Zionism is defined as, per Oxford Languages, “a movement for (originally) the re-establishment and (now) the development and protection of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel.” In simple terms, it is the belief that the state of Israel should exist in the nation that was once Palestine. It does not mean “uncritical support of Isreal”. While The Brutalist may hint at cynicisms that Israel cannot possibly deliver all that it promises, it never refutes the Zionist ideology. Even if it does not directly comment on if Israel should exist, it certainly depicts it as a place that its characters need. Most people in America believe in the morality of Israel defending itself, and so even if extending grace to the film, operating under the assumption that peoples individual morality will make sense of the themes, most will default to what they’ve already believed in and it will be the same Zionism the film textually upholds.

The film will reinforce that, yes, America’s failing had a heavy hand in the creation of Israel. But that is not an anti-Zionist idea, and it does not cast moral failing on the state of Israel. Importantly, the idea that the Israel as a state is necessary because Jewish refugees are not safe anywhere else has always been a tool of Zionist propaganda, even now. When the viewer already disagrees with Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people, America’s failure in the film instigates a cycle of violence. Then, the film becomes a bitter condemnation of the extense of American cruelty. But, to most, Israel’s brave existence is a respite against all anti-Jewish injustice. Within the context of the film, no cycle of violence is ever mentioned, so what is the audience meant to walk away with? If art does not challenge the common convention it engages with, it perpetuates it.