Thank you Netgalley for an advanced reader copy!

The Deep Sky by Yume Kitasei is classified as a sci-fi thriller, but it’s more meditative than that’d imply. Humanity’s crumbling into the sea, and in a last burst of hope, they launch 80 young adults into space to reach a new inhabitable planet. The crew of this journey has been training for the mission since they were 12, rigorously studying and growing up together, and now they inhabit a spaceship ten years from its destination. As the first phase of their mission begins, pregnancy and child rearing after a decade long hibernation, there is an explosion onboard- likely triggered by one of their own. Asuka, resilient but technically inadequate compared to her peers, survives the explosion and must discover who is culpable before they strike again.

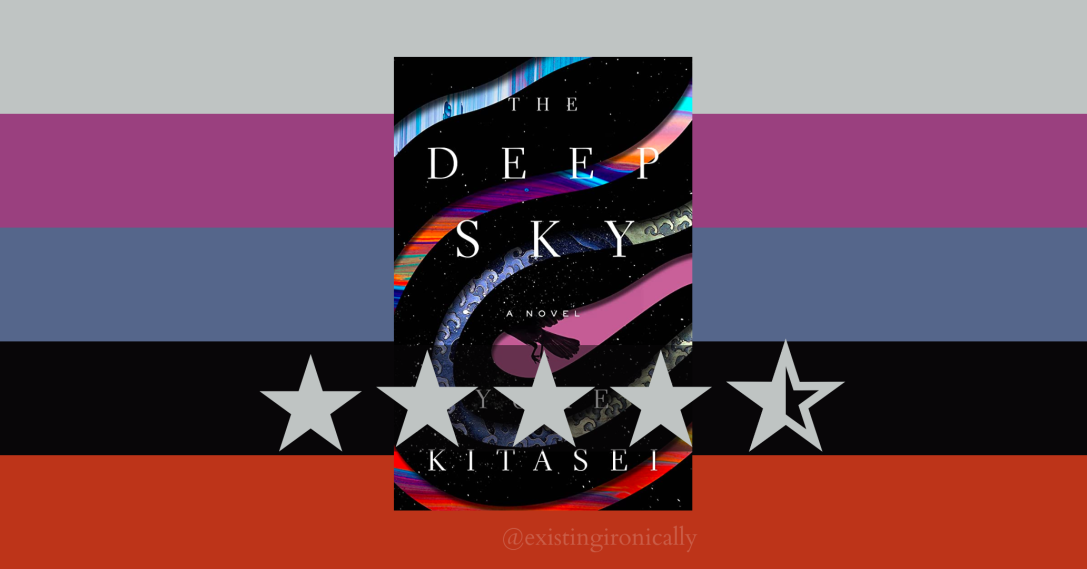

I really liked this book. Like. A lot. So let’s just start there. 4.5 stars rounded to a 4.

I’m probably going to bring up a decent bit of science fiction in this review. This is not to say that this book is trying to be like anything else, or that any of what I compare it to is better or worse, but it’s much easier to talk about a genre as varied as science fiction with a basis of bearing and a good point of comparison or connection.

Personally, I’m hesitant to call this a thriller because the plot doesn’t coax any feelings of doom or overwhelming dread. It does get exciting at parts, and you do believe that the crew is in genuine danger, but it’s a who-done-it whose detective genuinely does not believe that her peers want to cause her harm. Obviously, someone on the ship triggered the explosion, and yes people died, but from Asuka’s perspective, she doesn’t really see any of these people capable of harboring violent malice. The risks associated with the mission are on par with most sci-fi with a similar colonization premise, there are limited resources on the ship and no help in space, so if something goes wrong, it could mean certain death.

The direction The Deep Sky took is for the better. Personally, I don’t really need to see a group of women and other marginalized identities take any excuse to expose each other’s flaws and assume the worse. When they do point the finger in the book, it’s out of reluctance, if not desperation.

First quick round of comparisons. Regarding the ship and the crew, it has the same feel as Mickey7 by Edward Ashton. The protagonists of the stories could not be more dissimilar if they tried, but both books have the same sort of close-quarters crew from exceptional backgrounds who are very familiar with each other. The book is told with a split timeline similar to Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. While Project Hail Mary focused its flashbacks on Earth primarily as a means of interactive exposition, The Deep Sky uses it primarily as a way to build character and build a thematic throughline that extends past the ship. Honestly, I really enjoyed the split timeline. The book made excellent use of its format, the scenes Kitasei chooses to revisit are wonderfully actualized, and the split timeline model allows for the emotional beats to hold a hefty amount of weight. (Let’s go mommy issues! Everyone, give it up for mommy issues. Insecurity around close female friendships is second. Let’s go! Hitting all the marks.)

The writing was crisp and clear. The world and settings were well constructed. I quite enjoyed being in Asuka’s head. She’s a little rough around the edges, and frustrating at times, but impossible not to sympathize with or root for. I’m biracial as well, so I’m particularly fond of characters who grapple with similar dual identities. All the side characters are very defined with a good deal of complexity for an ensemble cast. The mystery itself isn’t terribly shocking, but it still manages to subvert expectations in a very satisfying way.

I could stop the review right here and say that it’s a good book and you should read it. Because I do believe that. It’s a well-constructed piece of science fiction, especially good for a debut, both stimulating and entertaining. It comments on the cynical world of today while projecting hope into tomorrow. The characters and conflict are well crafted and stick with the reader. Yes, it’s sci-fi, but the accessible kind that sticks close enough to Earth to feel entirely familiar. I hope this book gets big, and I hope that my words, in some way, accomplish that. I read this in the middle of a bad reading slump and breezed through it, impressed. I’m excited for what Kitasei does next.

But. Now. I want to talk about thematic. I have a lot to say. The Deep Sky has awakened the cogs in my brain, and unfortunately, I’m making that your (the reader’s) problem.

I decided to read this book while simultaneously watching the first 10 Star Trek movies for the first time over the course of a week. That may have done things to my brain. You’ll see in a moment.

Ursula K LeGuin, my queen, says in her forward to arguably one of the most famous sci fi novels, The Left Hand of Darkness, that science fiction is not a prediction of the future, but a reflection on the present. And true to the genre, the world Kitasei creates is nothing more than an exaggerated version of the world we currently live in. The climate crisis is out of control, sparking conflict between major nations. Extremist factions rise out of desperation, eco-terrorists and proto-MAGAS. And in the middle of all of this, some trillionaire decides to send 80 teenagers into space in an effort to save what’s left of humanity.

The question of if we should focus on the issues here first or use those resources to look forward is not new, in science fiction or in the real world. There were protests when the first Apollo Missions went up. Yes, the moon landing filled the world with the wonder of human capability and possibility, but it was funded to stick it to the USSR. It was a display of nationalism, meant to unite some people and scare others. We didn’t shoot for the moon to reach it, but to stick our flag in it first.

The current efforts of Bezos and Musk to develop commercial flights to space and colonize Mars are less of a space race and more a commodification of the space race. Billionaires would not be interested in technological development if they did not think that it was a means of furthering their wealth or retaining it in the face of human disaster. This is my personal interpretation of the situation, but I do believe it wholeheartedly because, by nature, to be a billionaire is to grow and maintain wealth and if any of these people deviated from that goal, they would no longer be billionaires.

The mission in the book is, from time to time, referred to as a vanity project by the trillionaire who funded it, but it’s impossible for me to believe in it beyond that. I want to see it as a signal of hope like the characters in the book, a measure of the tenacity of the human spirit and a projection of their capability, but I’m just too jaded. “Save humanity” is a noble goal, but humanity could either refer to the individual people composing all of human life or the vague concept of humans as a whole. Maybe it’s because I’m one of the people who would be left behind on the floating rock, but I really think we should be focusing on the floating rock.

In Star Trek: First Contact, we learn how space exploration (Starfleet) came to be. Basically, after World War III and devastating nuclear fallout, this one guy invents warp drive only with the intention of becoming rich. But in doing so, he unknowingly signals to alien life that humanity is advanced enough for interstellar travel, and aliens come to Earth and make first contact. After alien contact, the world unites, getting rid of money and their squabbles to focus on the betterment of humanity and developing Starfleet and the Federation to explore the galaxy. Sounds nice. Sounds good. I’m not sure why World War III was required to get there, but alright.

Importantly, Star Trek focuses on the expansion of humanity into space as something that goes hand in hand with world peace. We cannot focus outward without taking care of ourselves first. It refuses to make the choice between Earth and the cosmos. I love thinking and wondering about the possibility of human expansion into space, the possibilities that await us the farther we explore, but it’s impossible to imagine it as some sort of inspiration in the face of human collapse on Earth. I can’t do it.

Jeff Bezos shot Star Trek‘s William Shatner into space. If you don’t know much about Star Trek, Shatner plays Captain James Kirk, the original face of the franchise. He’s still around. As some sort of… publicity (?) stunt, Bezos decided to send him on a Blue Space Shuttle in 2021. You probably didn’t hear much about it, because the voyage didn’t exactly have its desired effect.

In an article Shatner wrote for Variety, he says:

“I love the mystery of the universe. I love all the questions that have come to us over thousands of years of exploration and hypotheses… but when I looked in the opposite direction, into space, there was no mystery, no majestic awe to behold . . . all I saw was death.

I saw a cold, dark, black emptiness. It was unlike any blackness you can see or feel on Earth. It was deep, enveloping, all-encompassing. I turned back toward the light of home… It was life. Nurturing, sustaining, life. Mother Earth. Gaia. And I was leaving her.

Everything I had thought was wrong. Everything I had expected to see was wrong.”

Keep in mind this was the guy who was on the show with the relatively hopeful take on things. He wasn’t in First Contact, but the vibes are pretty consistent. He recognized what I feel like all people should: that space is exciting, but our hopes lay in our home. I also implore you to read the article. Despite how you may feel about Shatner’s entries into the Star Trek canon, this Variety article is a truly good piece of writing.

I don’t think that The Deep Sky is any less of a book because I disagree with some of the ideas in it. There are some I do find compelling and enjoyed how the conclusions were reached in the book, like who “deserves” to be on such a mission. If anything, I’m grateful that the novel posed its conflict the way it did so I was able to have this conversation. What’s a conviction if you never have it challenged? If anything, the ideas in the novel are meant to be an open-ended aspiration, a vibe rather than any sort of moral determination. You can see both sides of the coin. This is just my reaction to it. Also, I just kind of wanted to talk about Star Trek. Read the book, so you can join in the conversation too.